13 Rocks You Won't Believe Aren't Man-Made!

Advertisement

2. Eye of the Sahara

For decades scientists, astronauts, and inquisitive spectators have been enthralled with the geological wonder known as the Richat Structure, often dubbed as the Eye of the Sahara. This enormous creation, found in the Sahara Desert close to Ouadane, Mauritania, is evidence of the Earth's capacity to produce breathtaking scenery by natural events. Known as "the Eye of the Sahara," the circular form and great scale of the structure—about 30 miles in diameter—make it obvious from distance.

At first, many specialists thought the precisely round form of the Eye of the Sahara resulted from a meteorite collision. Given the structure's similarity to recognized impact craters elsewhere on Earth, this idea looked reasonable. But as researchers dug more deeply, another narrative started to surface. Modern scientists now hold that the amazing formation we observe today was created totally by erosion, a process spanning millions of years.

Rising almost 650 feet above the nearby desert, the structure rests on an elevated platform. The development of the Eye has been much aided by this elevation differential. The Eye of the Sahara is, according to geologists, a quite severely degraded rock dome. A geologic dome is a kind of structural feature in which the oldest rocks are at the center and progressively younger rocks form rings moving outward from the center, bent into an anticlinal configuration.

About 600 million years ago, during the late Proterozoic to early Cambrian period, the Eye first developed. Significant geological activity in the area was resulting from the supercontinent Gondwana starting to split at this point. As magma rose from deep inside the Earth, the underlying sedimentary rocks bulged upward in a dome form.

Erosion has progressively removed the top layers of this dome over millions of years, revealing the circular rock foundation. The several rings seen in the Eye match the several kinds of rock that were first placed one on top of another. Ordovician sandstone makes up the outermost ring; advancing inward one finds strata of Proterozoic quartzites and other metamorphic rocks. A core of several igneous rocks—including rhyolitic volcanic rocks, gabbros, and carbonatites—lies at the very heart of the structure.

Differential erosion of these several rock types accentuates the special circular pattern of the Eye. Whereas weaker rocks erode more quickly and create valleys between the ridges, harder, more resistant rocks create ridges. Over millions of years, this process—shaped by wind, water, and temperature changes in the hostile desert environment—has continued.

Geologists and Earth scientists still find great appeal in the Eye of the Sahara. Its development offers important new perspectives on the geological processes sculpting our globe over very long times. Furthermore, for astronauts circling the Earth, the structure's obvious presence from space is significant. Many have said they passed across the great expanse of the Sahara Desert using the Eye as a compass.

The Eye of the Sahara draws brave visitors attracted by its exotic look and geological importance despite its far distance. But since the site is isolated and the surrounding desert conditions are severe, reaching there calls for meticulous planning and guided trips. The Eye of the Sahara is a wonderful evidence of the dynamic geological processes of the Earth and their capacity to produce amazing landscapes over millions of years as research on them keeps on.

Advertisement

Recommended Reading:

Mini Mischief Makers: Funny Moments Only Parents Get →

You are viewing page 2 of this article. Please continue to page 3

Stay Updated

Actionable growth insights, once a week. No fluff, no spam—unsubscribe anytime.

Advertisement

You May Like

10 Items You Should Never Put Down the Drain

08/14/2025

Unleashing The Power Of Vinegar: The Amazing Use You Must Try Now!

09/20/2025

Two Bananas Daily: Unexpected Health Benefits & Hidden Risks

10/26/2025

13 Craziest Laws You Won’t Believe Exist Worldwide

08/12/2025

What Your Nails Secretly Reveal About Your Health

09/03/2025

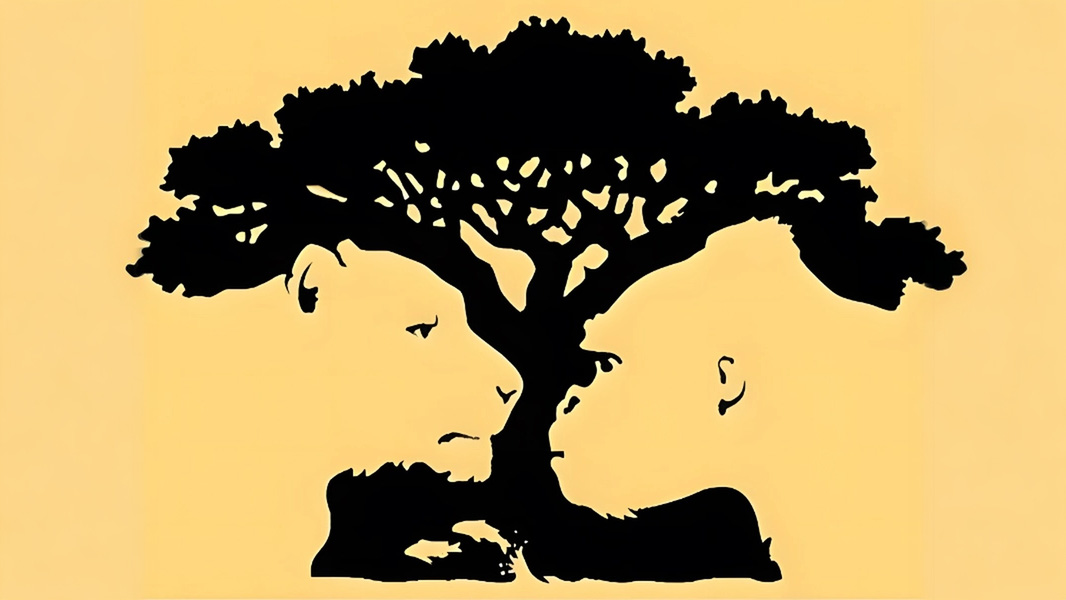

What You Notice First Reveals Your True Personality

10/12/2025

Perfect Timing: These Animal Photos Will Amaze You

09/18/2025

Cat Giant Kingdom: Exploring The Magical World Of 10 Largest Cat Animals

09/12/2025

20 Shocking Signs Your Marriage Might Be Doomed to Divorce

09/08/2025

30 Hilarious Animal Photos That Will Make You Smile

08/17/2025

25 Odd Wedding Photos Sure to Make You Laugh

10/25/2025

13 Weird Animals That Look Just Like Pokémon

09/03/2025

Pets Proving They're the Real Boss in Hilarious Photos

08/21/2025

Sleeping with Onions: My 7-Day Quest for Amazing Health Benefits

09/07/2025

Embarrassing Celebrity Wardrobe Fails Captured Live

10/04/2025

20 Loyal Dog Breeds That Protect You Fearlessly

10/23/2025

The Do’s And Don’ts Of Bringing Your Dog To Work

11/02/2025

Tanks and Sky-High Costs: The World's Priciest Military Wonders

09/12/2025

30 Most Audacious Cats Ever Caught in Action

10/04/2025

10+ Jaw-Dropping Photos That Shook the Internet

08/08/2025

Completely Interesting: Interesting Cat Photos Will Make You Smile

08/15/2025

24 Amazing Animals Right Before They Give Birth

10/02/2025

Priceless Pet Moments Showing Who's Actually Boss

09/10/2025

4 Sisters' 40-Year Photo Journey Will Amaze You with Stunning Changes

10/05/2025

Comments

MeridianScout · 08/08/2025

Open to instrumentation layering.